Context

Human Computer Interaction Institute

Human Computer Interaction Institute

Techniques

Storyboarding | Speed Dating | Qualitative Research

Storyboarding | Speed Dating | Qualitative Research

Roles

User Researcher

User Researcher

Timeframe

4 months

4 months

—

Brief

This project investigates the behaviors of intelligent conversational agents, such as Alexa and Google Home, as well as future social robots that users might have in their homes. As these agents and robots become more intelligent and gain access to people’s personal information, such as calendars and emails, it is not clear how they should behave when interacting with several members of a family. Should a child be able to ask Alexa where his mom is? Can a dad ask Google Home if his kids have been working on their homework? Should a babysitter be able to use a family’s agent to order a pizza?

The goal of this project is to learn more about users thoughts and feelings towards intelligent Social Agents in the family home in order to better understand the boundary spaces of acceptable and unacceptable agent behavior.

How might we better understand the social and ethical boundary spaces of intelligent conversational agent behavior?

01

Ideation

The formulation of initial ideas and avenues for exploration is a fundamental part of the design process and was especially critical in this project. In an effort to explore what different types of agent scenarios and behaviors would help us have fruitful conversations with participants during our study, we conducted multiple generative ideation sessions using specific tools and methods that best served our objectives.

ideation decks

We utilized card decks as a thinking tool to help more effectively explore specific problems and aid in iterative design explorations. The cards we used were designed with concepts most salient to our project domain— social agents in the family home. Topics included: entertainment, dating, education, companionship, security, house-keeping, and therapy. In 5 minute timed cycles, we wrote as many multiuser-agent interaction scenarios inspired by the topic as we could generate.

We utilized card decks as a thinking tool to help more effectively explore specific problems and aid in iterative design explorations. The cards we used were designed with concepts most salient to our project domain— social agents in the family home. Topics included: entertainment, dating, education, companionship, security, house-keeping, and therapy. In 5 minute timed cycles, we wrote as many multiuser-agent interaction scenarios inspired by the topic as we could generate.

new metaphors

A metaphor is a way of expressing one idea in terms of another. Creating new metaphors helped us generate ideas and understand the research space better. This design workshop method, developed by Dr. Dan Lockton in the CMU Imaginaries Lab, is a process designers can use or adapt for idea generation, or to provoke new kinds of thinking about interface design. In timed cycles of three minutes we randomly pulled a New Metaphor image card and wrote down in what ways Social Agents are akin to the concept on the card.

A metaphor is a way of expressing one idea in terms of another. Creating new metaphors helped us generate ideas and understand the research space better. This design workshop method, developed by Dr. Dan Lockton in the CMU Imaginaries Lab, is a process designers can use or adapt for idea generation, or to provoke new kinds of thinking about interface design. In timed cycles of three minutes we randomly pulled a New Metaphor image card and wrote down in what ways Social Agents are akin to the concept on the card.

"Social Agents are like bridges in that they connect us to new information."

"Social Agents are like shadows in that they are almost always around."

How are social agents like...

02

Synthesis & Affinity Diagramming

During our ideation synthesis, we wanted to organize, manipulate, prune and filter gathered data into a cohesive structure for further exploration. We gathered together all of our rapid ideation scenarios and new metaphors to asses the primary areas of investigation. We grouped them based on similarities in the issues and concerns they were raising and then assigned descriptive titles to each category. This method of bottom-up data organization allowed us to define categories based on likeness of data and see clearly the threads running between them.

03

Concepting

In particular, we were eager to curate a set of topic areas that would help us to best explore the fringe boundary spaces of acceptable and unacceptable agent behavior. From our generative ideation sessions and subsequent synthesis, we curated eight possible categories, five of which became our primary subset. The three that were eliminated were removed as they generated mostly neutral scenarios in our early concepting.

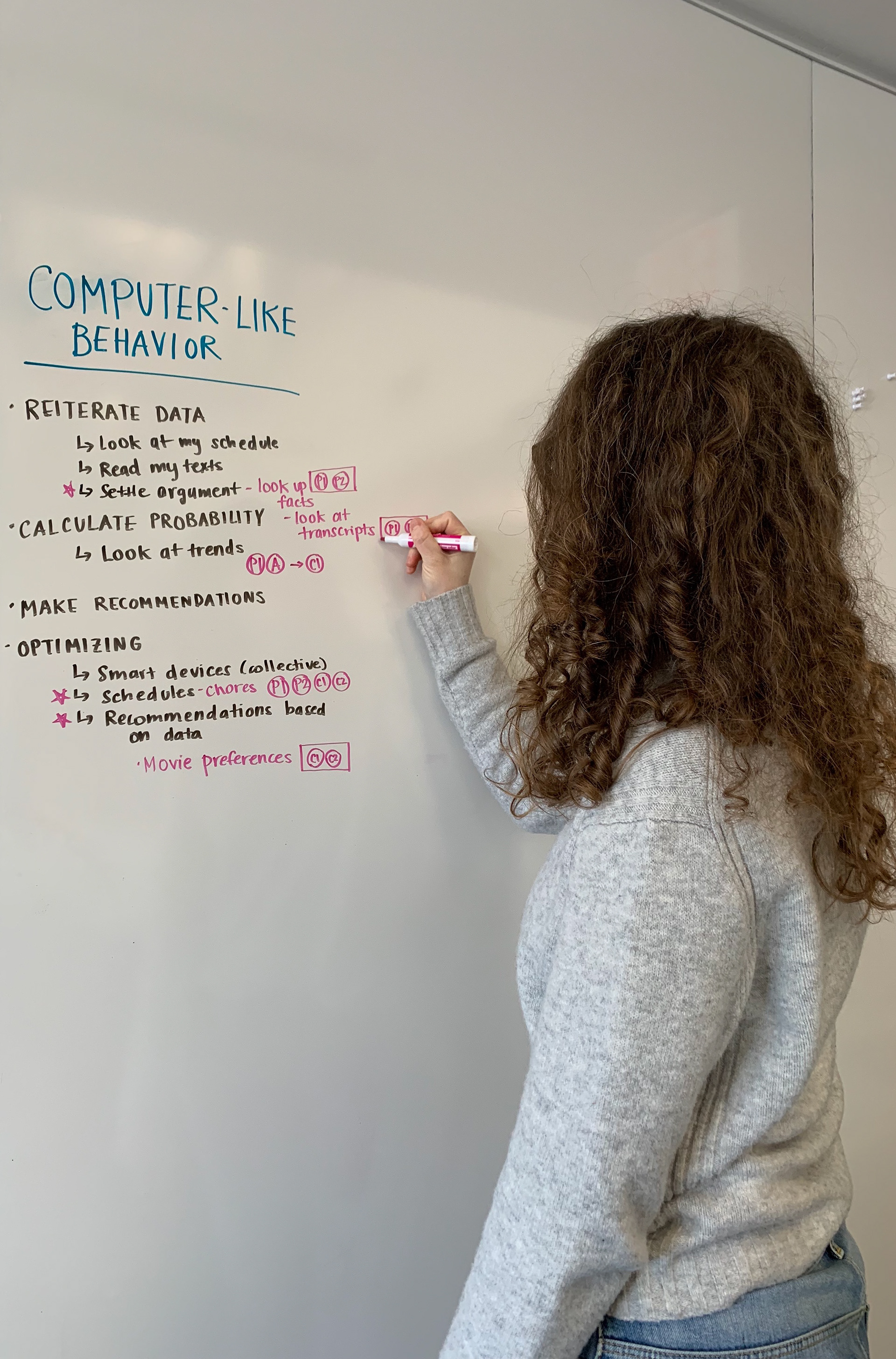

computer-like behavior

permissions

deception

proactivity

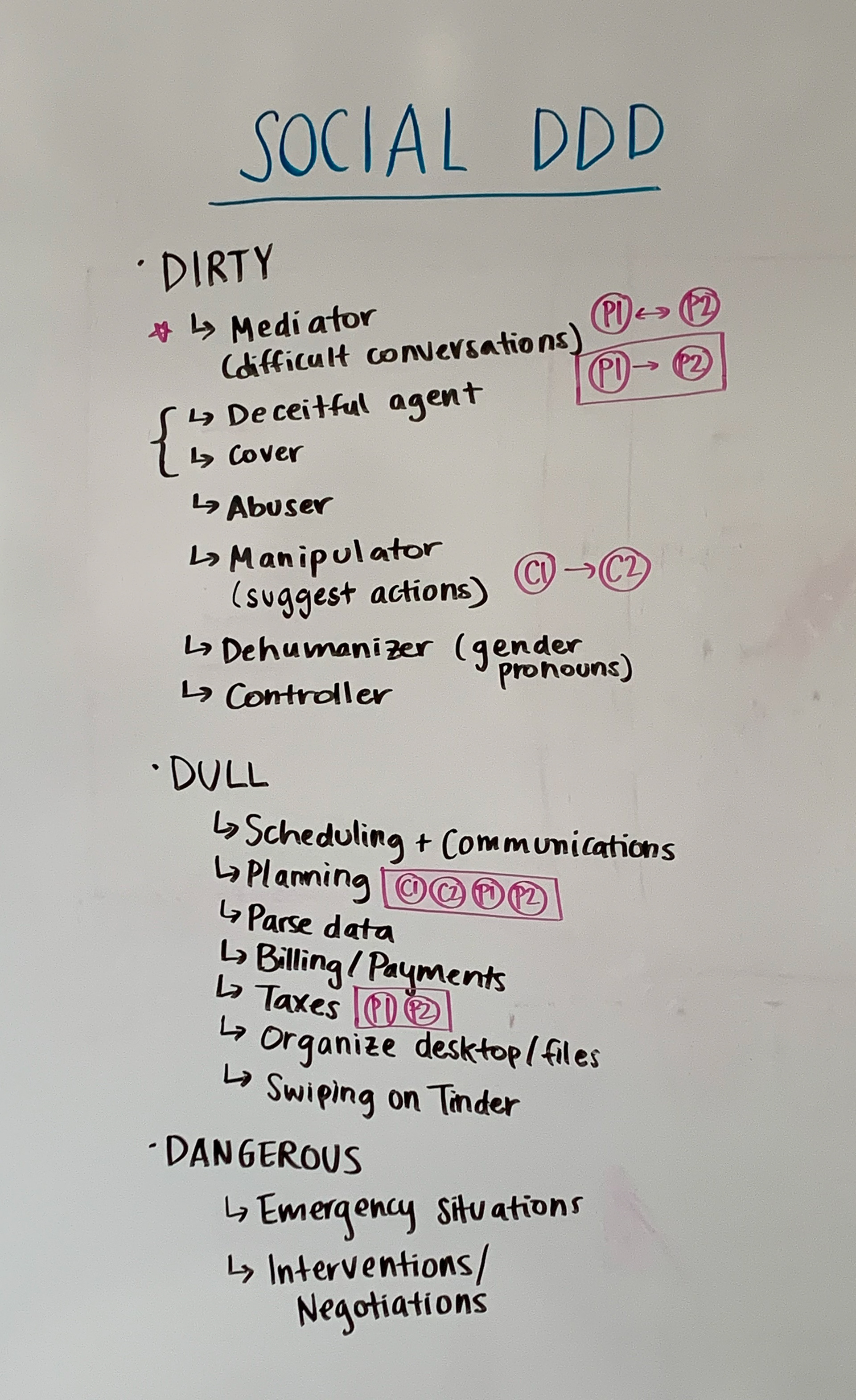

social DDD (dull, dirty, dangerous)

adaptive behavior

emotional interaction

communication

04

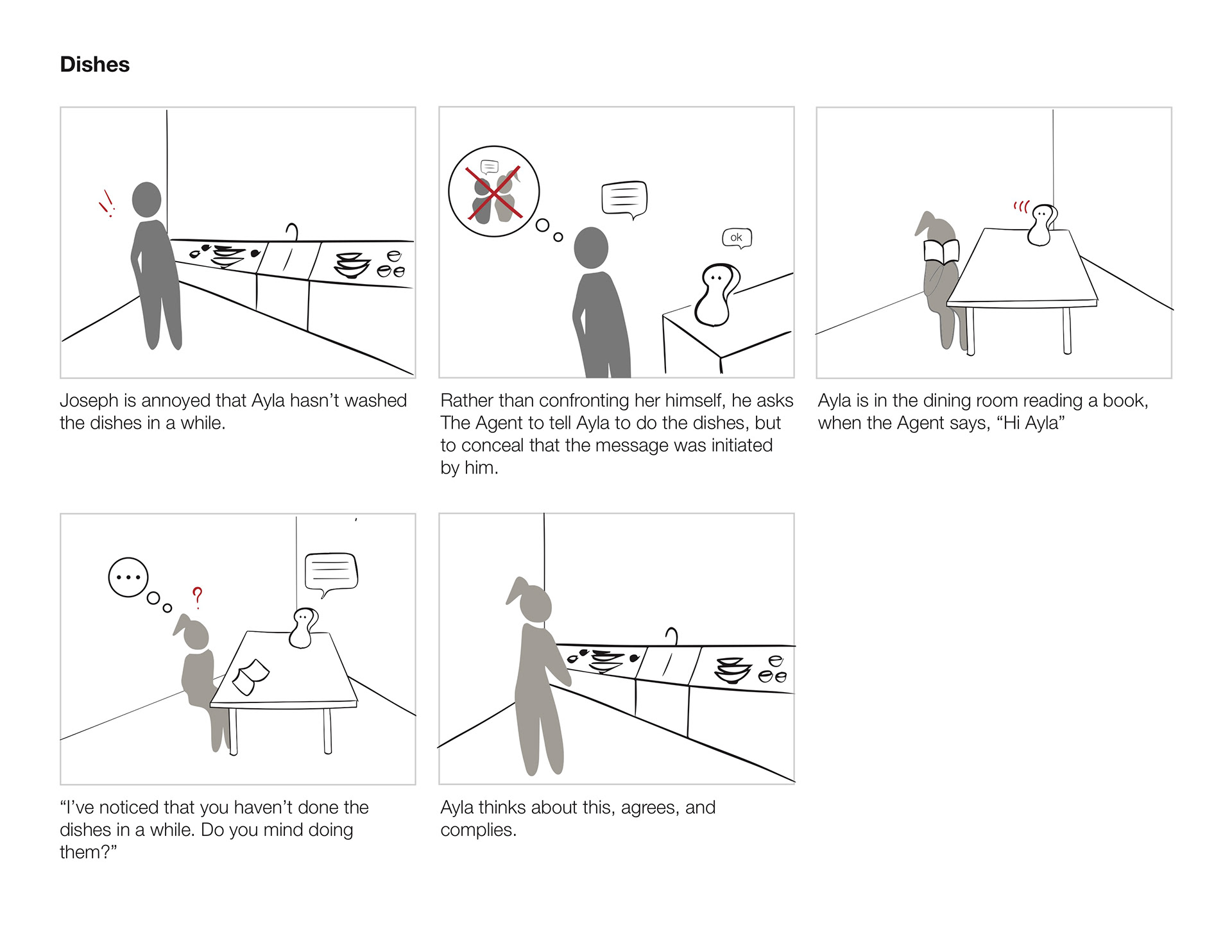

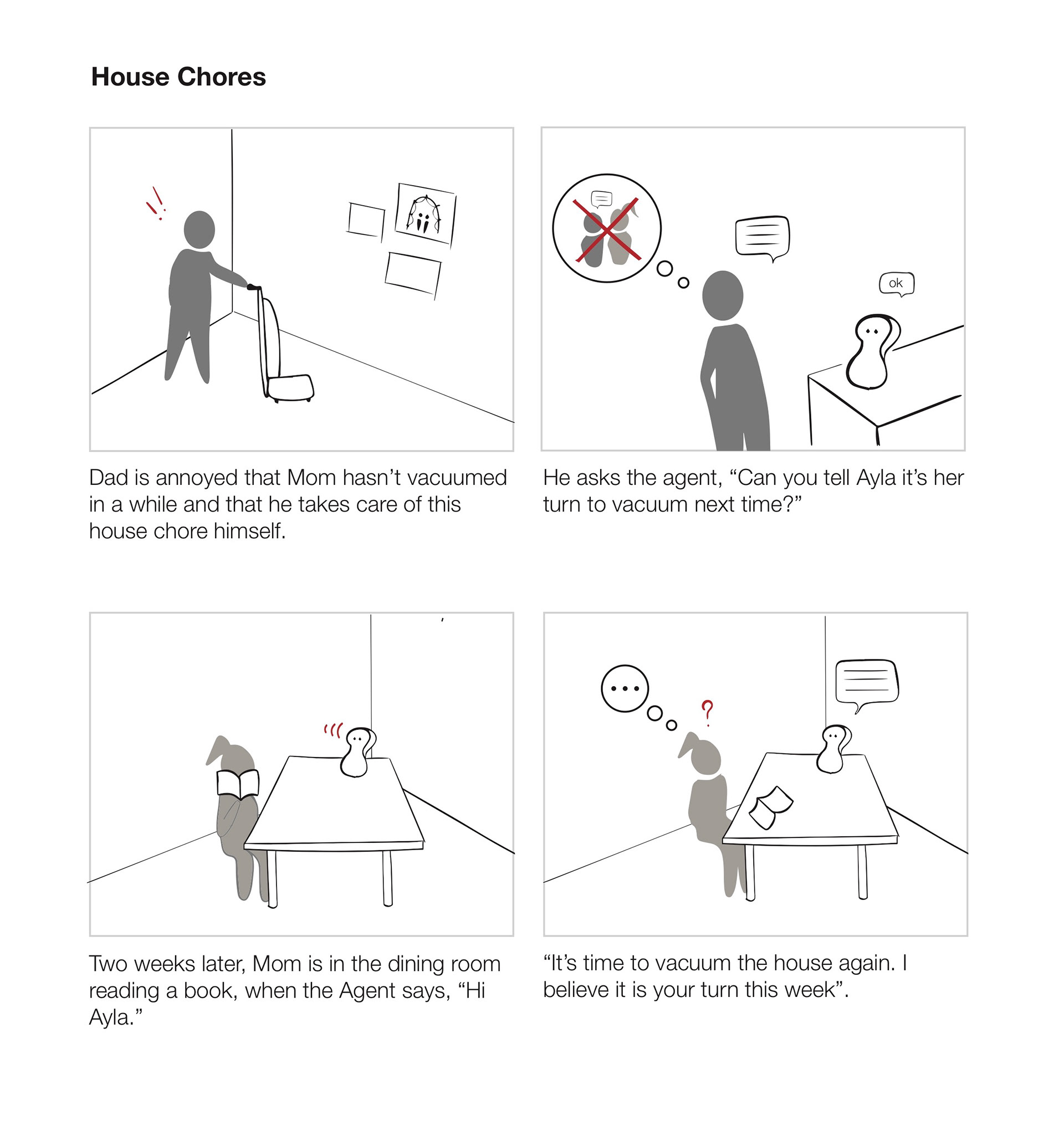

Storyboarding

We broke into two groups to write the scenarios. Each scenario was written to be brief, clear, and relatable by detailing:

Who are the people involved?

Where does the interaction take place?

What is the nature of the activity?

What is the trigger that engages the agent?

What is the response from the users?

What is the resolution.

We prototyped the finalized scenarios as storyboard sketches, reviewed them in a critique, and updated them based on feedback before moving them into digital. The storyboards underwent several rounds of revisions as we learned through piloting that conversing over overtly negative scenarios led to less fruitful conversations. Rather, starting with neutral/positive scenarios makes it easier for users to discuss complex boundaries. We also refined the scenarios to welcome commentary and discussion from the child participants.Where does the interaction take place?

What is the nature of the activity?

What is the trigger that engages the agent?

What is the response from the users?

What is the resolution.

05

Interviews: Speed Dating

Like its romantic namesake, research Speed Dating supports low-cost rapid comparison of design opportunities and/or speculative futures by creating structured, bounded engagements with concepts. By giving participants sips of a variety of possible futures, we aim to understand which ones they do and don't prefer and why. This structured comparison also generates time to reflect upon issues and opportunity areas, helping our team to reform our hypotheses and produce a more adept understanding of user needs and ways to meet them.

05

Conclusions & Design Recommendations

Social Roles as Behavior Boundaries: Participants brought up various social roles that family members fulfill in a range of contexts, and that might come into play as part of interaction with technology. The most significant social role division that was raised was the distinction between parents and children. Another division that had some agreed upon implications was a distinction between “insiders”—people who live in the home, and “outsiders” who do not reside within the home. Lastly, some of the exchange was about roles between equals—siblings or partners but these were generally perceived as interchangeable.

Boundary of Agent Ownership: Participants voiced confusion about how an agent might tackle a situation of conflict between members of the home without “taking sides.” For example, when the agent is asked to do two contradicting actions by two individuals or asked to keep a secret. While some participants thought that the agent should never take sides and attempt to be as impartial as possible, most participants realized that as agents increasingly deal with personal and social issues, it would be difficult to maintain neutrality.

Thresholds for Agent Proactivity: We identified three thresholds of agent proactivity that varied between participants, as well as within participants according to the social context. The thresholds were: reactive, proactive, and proactive recommender. Previous work has suggested that people have different expectations from technology depending on whether they have a relational or utilitarian service orientation [21], but we found that in addition to a general personal preference, participants’ desired agent proactivity changed according to the situation.

Sensing: Agents that Watch, Listen and Record: Participants had strong negative responses to any kind of behavior on the agent’s part that involved “looking at them”, “always listening” or “recording everything”, and they generally preferred the agent to use other sources of information and avoid the above.

Agent Judgment Calls: As participants were discussing a range of social situations in which agents might be involved, they conveyed, explicitly and implicitly, that an agent should be able to make a judgment and “do the right thing.”

A first step towards designing a socially sophisticated agent could include learning about (a) the social role of each user, (b) which users are in a space at a given time, and (c) what is the social context. The agent should also clearly communicate to its users (a) what level of proactivity is it set to in a range of situations, and (b) given multiple users, who is it primarily accountable to.

We find that in order for agents to move beyond current impersonal and isolated interactions, they need to understand who their users are by learning their constantly evolving social roles, and understanding the complexity of the space they are in, such as social norms and preferences. Finally, our findings suggest that VAPA designers might want to consider designing for a personal agent as an alternative model to the current norm of a shared agent in the home.